Ancient Wetlands Swamp 28th Street Subway Yet Again as Storms Outpace Sewers

As climate-fuelled storms converge with ancient Manhattan wetlands, New York’s infrastructure battles the ghosts of geography — and the city’s future resilience is at stake.

It is a sight both spectacular and troubling: water erupting through a manhole cover at Manhattan’s 28th Street subway station, jetting skyward as though a subterranean geyser lurked beneath the city. On July 15th, as more than two inches of rain battered New York within a single, tempestuous hour, commuters at the Broadway–Seventh Avenue line witnessed—and waded through—yet another aquatic display. For many, this was déjà vu. Others simply asked: why here, and why again?

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) chair, Janno Lieber, was quick to apportion blame to the city’s ancient sewer system. Designed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this subterranean network routinely faces challenges from modern storms, particularly as climate change prompts rainfall of greater intensity and unpredictable frequency. Yet data reveal that the vast majority of subway stations weathered Monday’s deluge with barely a puddle to show for it, suggesting that older pipes are not the sole villain.

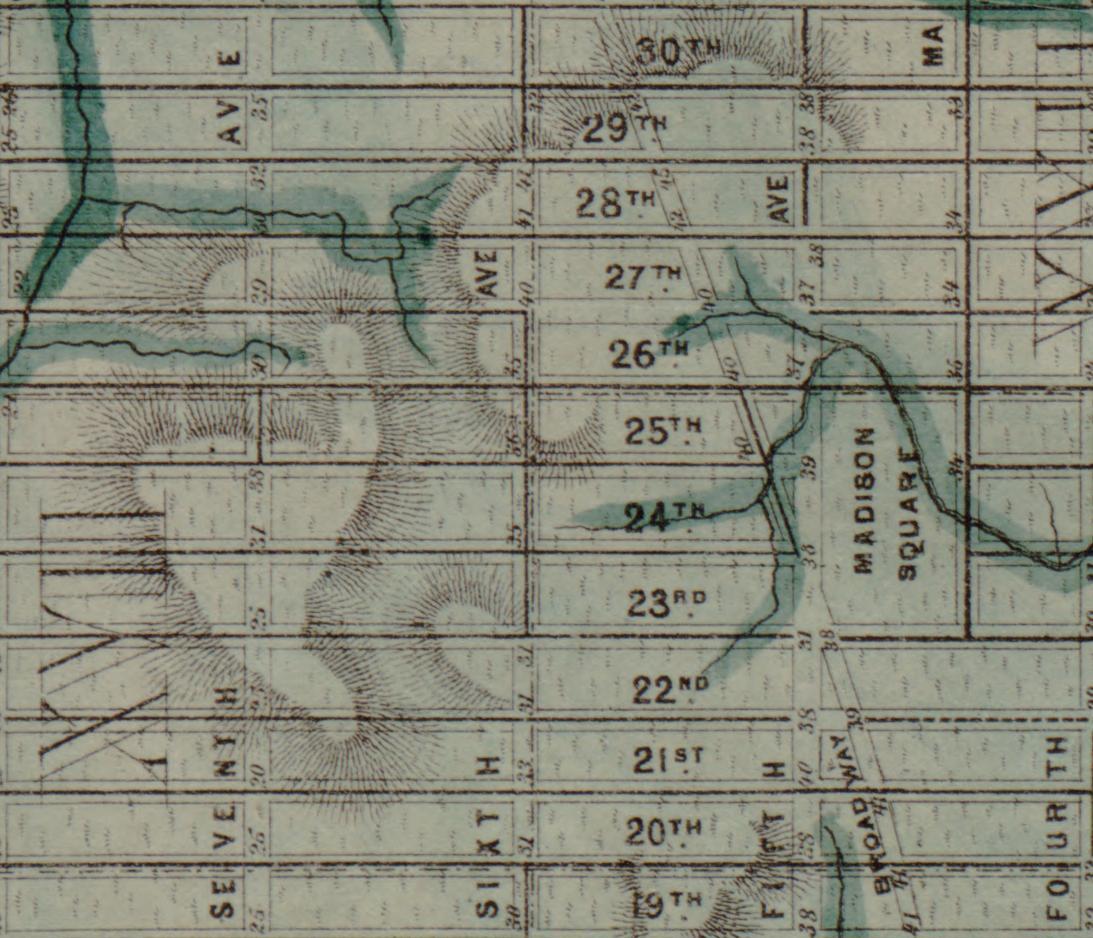

The answer, it seems, traces back to Manhattan’s primordial underbelly. Long before the advent of glass and steel, the intersection at 28th Street and Seventh Avenue was not concrete but marshland—one node in a web of wetlands and flow paths, as outlined in an 1865 city topography. As Eric Sanderson of the New York Botanic Garden’s Center for Conservation and Restoration Ecology remarks, paving and filling the marsh “only made flooding worse.” Nature’s tendency remains stubborn: “Water, just as it always has done, runs downhill.”

It is worth noting that roughly 20% of New York City—so-called “blue zones”—sits atop ground that was always predisposed to ponding. As new storms buffet the city with greater force, the ghosts of Manhattan’s watery past assert themselves. A wetland paved over does not forget; it simply waits, quietly destabilizing whatever human ingenuity builds atop it.

The immediate implications are as practical as they are pressing. For the MTA, recurrent geysers at 28th Street portend escalating bills for damage control, patron inconvenience, and service suspensions. Flooding not only undermines track integrity but hastens the decay of cables and switches—practical headaches for America’s busiest public transit system, which ferried over three million people daily even in the pandemic’s wake.

Downstream effects, however, reach beyond transport. Residential basements, likewise built atop the city’s blue memory, flood with increasing regularity, imposing puny insurance payouts and considerable distress on households. Businesses, small and large, factor escalating flood risks into their location decisions; so, soon enough, will banks and underwriters. As climate models project New York’s future as wetter and occasionally tempestuous, the economics of living and working in flood-prone zones take on a new, decidedly less buoyant tone.

At a political level, the question is not just how to stem the floodwaters, but for whom. As Sanderson archly observes, “Are you going to let other parts of the city flood and then protect this part of the city?” This uncomfortable equity dilemma recurs each time infrastructure upgrades are mooted. Retrofit the sewers beneath Midtown, and less fashionable neighbourhoods may remain vulnerable. As billions are already earmarked for coastal resiliency efforts—think the $1.45 billion East Side Coastal Resiliency Project—competition over limited dollars promises only to grow more heated.

New York’s soggy problem is hardly unique. London, which famously built the Thames Barrier to keep the North Sea at bay, routinely flirts with disaster as rainfall overwhelms ancient Victorian drains. Tokyo has invested in bracingly expensive underground flood tunnels. The Dutch, of course, have raised water management to a fine art. But even in these cases, adaptation is a moving target: historic city grids and the grandeur of old engineering ensure perfectly watertight fixes remain elusive.

The costs of ignoring history

Unlike its European peers, New York’s approach to subterranean water feels both pragmatic and perennially incremental—reactive, rather than visionary. Proposals to overhaul vast stretches of the city’s sewers run into astronomical price tags and political headwinds. Tearing up streets, relocating businesses, and retrofitting miles of main are the sort of disruptions that make even seasoned urban planners blanch. Yet, as climate forecasts grow grimmer, “hoping it’s big enough,” as Sanderson puts it, edges into the realm of magical thinking.

There are lessons to be taken from cities that have, at significant expense, attempted to live with their topography rather than deny it. Urban wetlands can serve as sponges, and green infrastructure—permeable pavements, bioswales, and rain gardens—can slow water’s rush. Such schemes, while less photogenic than doughtily sandbagging subway entrances, might incidentally revive bits of Manhattan’s long-buried natural heritage and afford citizens a rare glimpse of what once was.

In practical terms, New York would do well to marshal its formidable ingenuity toward both adaptation and mitigation. Halting climate change may be the stuff of international negotiations, but ensuring that the city’s residents are not wading through “mini swimming pools” in order to catch the 1 train is a decidedly municipal task. The city’s challenge lies not so much in denying nature, but in accommodating it—however grudgingly.

The flooding at 28th Street stands as both a cautionary tale and a call to action. New Yorkers have long boasted of the city’s capacity to outbuild, outthink, and, when necessary, outlast its adversaries. But in this case, the adversary is neither external nor new: it is the city’s own forgotten landscape, reasserting itself with every torrential downpour. If New York is to remain resilient, it must reckon candidly with the persistent work of gravity, water, and time.

Subterranean geysers may briefly amuse curious commuters, but they herald a future where the city meets an ancient geography on terms not entirely of its choosing. The lessons are neither revolutionary nor particularly novel, but the price of willful amnesia only climbs. In the long run, as the experts say, you cannot deny nature. The sooner the city’s planners, and its citizens, accept this fact, the better equipped New York will be for the storms that lie ahead. ■

Based on reporting from Gothamist; additional analysis and context by Borough Brief.